Here is a guide to punctuation.

|

What is punctuation? Answer How many punctuation marks are there? Answer What are various punctuation marks and signs? Answer What are most common punctuation marks? Answer When to use punctuation marks? Answer What do you know about English language punctuation?Answer What should you know about English language punctuation? Answer Why do we need to punctuate? Answer Where will you use apostrophes in an English sentence?Answer Will you use apostrophes with masters and bachelors?Answer What is the reason?Answer When do you use a comma or dash in an English sentence?Answer Where do you use quotation marks in in an English sentence?Answer What is the difference in usage of colon and semicolon in an English sentence?Answer How do I use the comma? Answer What are the rules of capitalization? Answer How do I use the apostrophe correctly? Answer How many spaces should I leave after a period or other concluding mark of punctuation?Answer What are various punctuation marks in the English language?Answer Can you write English language sentences without an apostrophe, dash, or quotation mark?Answer Why should you avoid using apostrophe, dash, or quotation marks while writing English language?Answer What are various punctuation marks in the English language?Answer Can you write English language sentences without an apostrophe, dash, or quotation mark?Answer Why should you avoid using apostrophe, dash, or quotation marks while writing English language?Answer Why was there need to write this guide?Answer Why do some English language documents not require much punctuation? Answer What is the purpose of punctuation?Answer What are some of the examples?Answer Does this type of punctuation separate words into sentences, clauses, and phrases in order to clarify meaning?Answer Should you use punctuation marks more than required?Answer What will happen if you use punctuation marks more than required?Answer What punctuation marks or signs have been verified (as of September 10, 2012) to cause errors when read by computers and on the Internet?Answer What is an example of non-required punctuation?Answer Is there a need to add • (a bullet point) before a word, words, or sentences?Answer Does this type of punctuation fulfill the purpose to clarify meaning of a word, words, or sentences?Answer Is there a need to add • (a bullet point) before various words? Answer Why do you need to add • (a bullet point) before various words? Answer |

Punctuation

Here is a guide to punctuation.

|

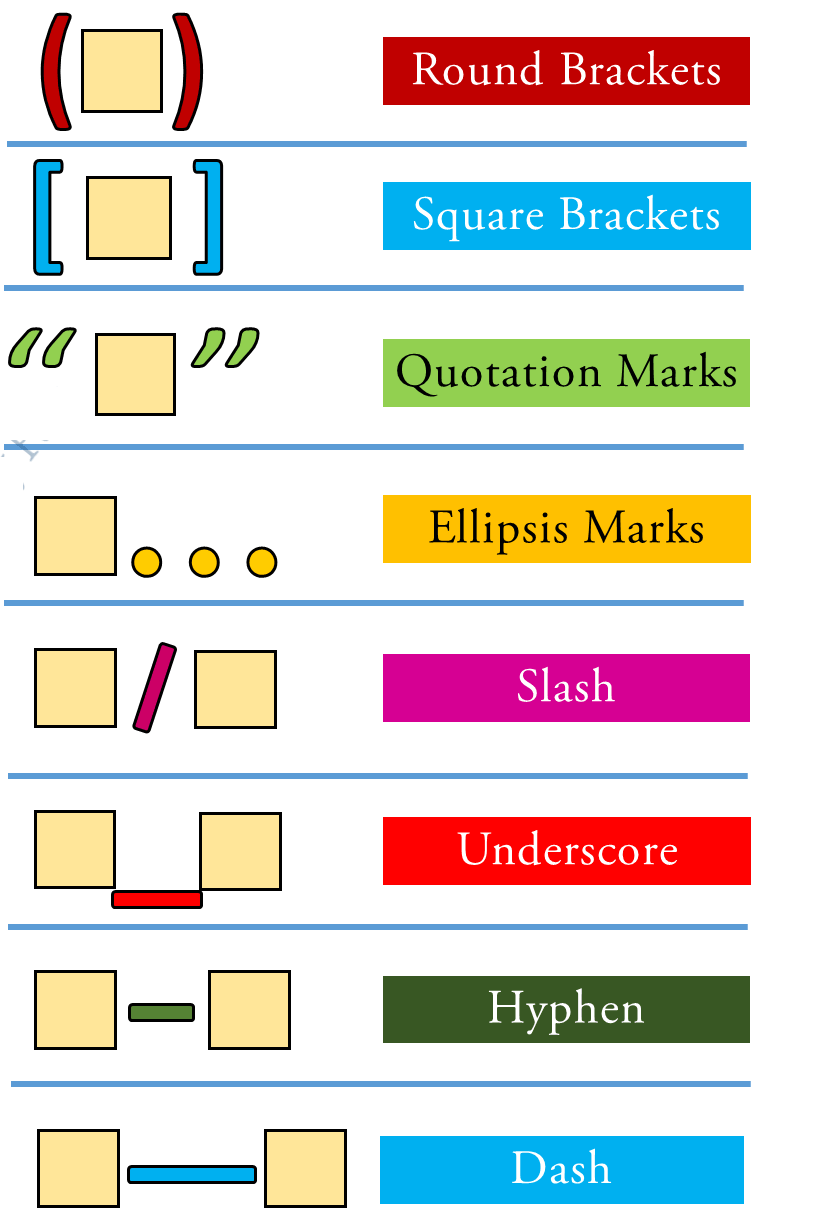

What is punctuation? Punctuation is the use of standard marks and signs in writing and printing to separate words into sentences, clauses, and phrases in order to clarify meaning. How many punctuation marks are there? At least 27. What are various punctuation marks and signs? What are most common punctuation marks? Some common punctuation marks are the period, comma, question mark, exclamation point, apostrophe, quotation mark and hyphen.

Why do some English language documents not require much punctuation?

Why do some English language documents not require much punctuation?

Punctuation should fulfill the purpose of the particular communication; sometimes meaning is best communicated with minimal punctuation. Why was there need to write this guide? Some people do not punctuate their English language documents at all. Some people punctuate their English language documents more than necessary. With computers and the Internet, some punctuation marks and signs tend to be used incorrectly. What is the purpose of punctuation? To separate words into sentences, clauses, and phrases with specific emphases, which helps clarify meaning. What are some of the examples? Some people add a bullet point before every word or sentence in a list. Does this type of punctuation separate words into sentences, clauses, and phrases in order to clarify meaning? No, it doe not. An editor added 75 bullet point before various words and sentences on a page. The computer counted these bullet points as 75 extra words. Adding bullet points before words or sentence did not add or clarify the meaning of the document, but it padded the word count. Should you use punctuation marks more than required? No, you should not. What will happen if you use punctuation marks more than required? It will cause confusion for others. Some punctuation (such as the instance of bullets given earlier) can be misinterpreted (by the computer in the instance given earlier, but by human readers as well). What punctuation marks or signs have been verified (as of September 10, 2012) to cause errors when read by computers and on the Internet? These are computer server operations issues. What is an example of non-required punctuation? The bullet point. Is there a need to add • (a bullet point) before a word, words, or sentences? No. Does this type of punctuation fulfill the purpose to clarify meaning of a word, words, or sentences? No. Do not use unnecessary punctuation. If any punctuation does not help in writing and printing to separate words into sentences, clauses, and phrases in order to clarify meaning, then that punctuation is not required. Is there a need to add • (a bullet point) before various words? No. Why do you need to add • (a bullet point) before various words? You do not need to add a bullet point. | |||||||||

| What are various punctuation marks and signs? | |||||||||

|

|

Rule 1a. Use the apostrophe to show possession. To show possession with a singular noun, add an apostrophe plus the letter s. Examples: Rule 1b. Many common nouns end in the letter s (lens, cactus, bus, etc.). So do a lot of proper nouns (Mr. Jones, Texas, Christmas). There are conflicting policies and theories about how to show possession when writing such nouns. There is no right answer; the best advice is to choose a formula and stay consistent. Rule 1c. Some writers and editors add only an apostrophe to all nouns ending in s. And some add an apostrophe + s to every proper noun, be it Hastings's or Jones's. One method, common in newspapers and magazines, is to add an apostrophe + s ('s) to common nouns ending in s, but only a stand-alone apostrophe to proper nouns ending in s. Examples: Care must be taken to place the apostrophe outside the word in question. For instance, if talking about a pen belonging to Mr. Hastings, many people would wrongly write Mr. Hasting's pen (his name is not Mr. Hasting). Correct: Mr. Hastings' pen Another widely used technique is to write the word as we would speak it. For example, since most people saying, "Mr. Hastings' pen" would not pronounce an added s, we would write Mr. Hastings' pen with no added s. But most people would pronounce an added s in "Jones's," so we'd write it as we say it: Mr. Jones's golf clubs. This method explains the punctuation of for goodness' sake. Rule 2a. Regular nouns are nouns that form their plurals by adding either the letter s or -es (guy, guys; letter, letters; actress, actresses; etc.). To show plural possession, simply put an apostrophe after the s. Correct: guys' night out (guy + s + apostrophe) Incorrect: guy's night out (implies only one guy) Correct: two actresses' roles (actress + es + apostrophe) Incorrect: two actress's roles Rule 2b. Do not use an apostrophe + s to make a regular noun plural. Incorrect: Apostrophe's are confusing. Correct: Apostrophes are confusing. Incorrect: We've had many happy Christmas's. Correct: We've had many happy Christmases. In special cases, such as when forming a plural of a word that is not normally a noun, some writers add an apostrophe for clarity. Example: Here are some do's and don'ts. In that sentence, the verb do is used as a plural noun, and the apostrophe was added because the writer felt that dos was confusing. Not all writers agree; some see no problem with dos and don'ts. Rule 2c. English also has many irregular nouns (child, nucleus, tooth, etc.). These nouns become plural by changing their spelling, sometimes becoming quite different words. You may find it helpful to write out the entire irregular plural noun before adding an apostrophe or an apostrophe + s. Incorrect: two childrens' hats The plural is children, not childrens. Correct: two children's hats (children + apostrophe + s) Incorrect: the teeths' roots Correct: the teeth's roots Rule 2d. Things can get really confusing with the possessive plurals of proper names ending in s, such as Hastings and Jones. If you're the guest of the Ford family—the Fords—you're the Fords' guest (Ford + s + apostrophe). But what if it's the Hastings family? Most would call them the "Hastings." But that would refer to a family named "Hasting." If someone's name ends in s, we must add -es for the plural. The plural of Hastings is Hastingses. The members of the Jones family are the Joneses. To show possession, add an apostrophe. Incorrect: the Hastings' dog Correct: the Hastingses' dog (Hastings + es + apostrophe) Incorrect: the Jones' car Correct: the Joneses' car In serious writing, this rule must be followed no matter how strange or awkward the results. Rule 2e. Never use an apostrophe to make a name plural. Incorrect: The Wilson's are here. Correct: The Wilsons are here. Incorrect: We visited the Sanchez's. Correct: We visited the Sanchezes. Rule 3. With a singular compound noun (for example, mother-in-law), show possession with an apostrophe + s at the end of the word. Example: my mother-in-law's hat If the compound noun (e.g., brother-in-law) is to be made plural, form the plural first (brothers-in-law), and then use the apostrophe + s. Example: my two brothers-in-law's hats Rule 4. If two people possess the same item, put the apostrophe + s after the second name only. Example: Cesar and Maribel's home is constructed of redwood. However, if one of the joint owners is written as a pronoun, use the possessive form for both. Incorrect: Maribel and my home Correct: Maribel's and my home Incorrect: he and Maribel's home Incorrect: him and Maribel's home Correct: his and Maribel's home In cases of separate rather than joint possession, use the possessive form for both. Examples: Rule 5. Use an apostrophe with contractions. The apostrophe is placed where a letter or letters have been removed. Examples: doesn't, wouldn't, it's, can't, you've, etc. Incorrect: does'nt Rule 6. There are various approaches to plurals for initials, capital letters, and numbers used as nouns. Examples: Many writers and editors prefer an apostrophe after single capital letters only: Examples: There are different schools of thought about years and decades. The following examples are all in widespread use: Examples: Awkward: the '90's Rule 7. Amounts of time or money are sometimes used as possessive adjectives that require apostrophes. Incorrect: three days leave Correct: three days' leave Incorrect: my two cents worth Correct: my two cents' worth Rule 8. The personal pronouns hers, ours, yours, theirs, its, whose, and oneself never take an apostrophe. Example: Feed a horse grain. It's better for its health. Rule 9. When an apostrophe comes before a word or number, take care that it's truly an apostrophe (’) rather than a single quotation mark (‘). Incorrect: ‘Twas the night before Christmas. Correct: ’Twas the night before Christmas. Incorrect: I voted in ‘08. Correct: I voted in ’08. NOTE Serious writers avoid the word 'til as an alternative to until. The correct word is till, which is many centuries older than until. Rule 10. Beware of false possessives, which often occur with nouns ending in s. Don't add apostrophes to noun-derived adjectives ending in s. Close analysis is the best guide. Incorrect: We enjoyed the New Orleans' cuisine. In the preceding sentence, the word the makes no sense unless New Orleans is being used as an adjective to describe cuisine. In English, nouns frequently become adjectives. Adjectives rarely if ever take apostrophes. Incorrect: I like that Beatles' song. Correct: I like that Beatles song. Again, Beatles is an adjective, modifying song. Incorrect: He's a United States' citizen. Correct: He's a United States citizen. Rule 11. Beware of nouns ending in y; do not show possession by changing the y to -ies. Correct: the company's policy Incorrect: the companies policy Correct: three companies' policies |

Colons

|

A colon means "that is to say" or "here's what I mean." Colons and semicolons should never be used interchangeably. Rule 1. Use a colon to introduce a series of items. Do not capitalize the first item after the colon (unless it's a proper noun). Examples: Rule 2. Avoid using a colon before a list when it directly follows a verb or preposition. Incorrect: I want: butter, sugar, and flour. Correct: Incorrect: I've seen the greats, including: Barrymore, Guinness, and Streep. Correct: I've seen the greats, including Barrymore, Guinness, and Streep. Rule 3. When listing items one by one, one per line, following a colon, capitalization and ending punctuation are optional when using single words or phrases preceded by letters, numbers, or bullet points. If each point is a complete sentence, capitalize the first word and end the sentence with appropriate ending punctuation. Otherwise, there are no hard and fast rules, except be consistent. Examples:

The following are requested:

These are the pool rules:

Rule 4. A colon instead of a semicolon may be used between independent clauses when the second sentence explains, illustrates, paraphrases, or expands on the first sentence. Example: He got what he worked for: he really earned that promotion. If a complete sentence follows a colon, as in the previous example, it is up to the writer to decide whether to capitalize the first word. Although generally advisable, capitalizing a sentence after a colon is often a judgment call. Note: A capital letter generally does not introduce a simple phrase following a colon. Example: He got what he worked for: a promotion. Rule 5. A colon may be used to introduce a long quotation. Some style manuals say to indent one-half inch on both the left and right margins; others say to indent only on the left margin. Quotation marks are not used. Example: The author of Touched, Jane Straus, wrote in the first chapter: Rule 6. Use a colon rather than a comma to follow the salutation in a business letter, even when addressing someone by his or her first name. (Never use a semicolon after a salutation.) A comma is used after the salutation in more informal correspondence. Formal: Dear Ms. Rodriguez: Informal: Dear Dave, |

Commas

|

Commas and periods are the most frequently used punctuation marks. Commas customarily indicate a brief pause; they're not as final as periods. Rule 1. Use commas to separate words and word groups in a simple series of three or more items. Example: My estate goes to my husband, son, daughter-in-law, and nephew. Note: When the last comma in a series comes before and or or (after daughter-in-law in the above example), it is known as the Oxford comma. Most newspapers and magazines drop the Oxford comma in a simple series, apparently feeling it's unnecessary. However, omission of the Oxford comma can sometimes lead to misunderstandings. Example: We had coffee, cheese and crackers and grapes. Adding a comma after crackers makes it clear that cheese and crackers represents one dish. In cases like this, clarity demands the Oxford comma. We had coffee, cheese and crackers, and grapes. Fiction and nonfiction books generally prefer the Oxford comma. Writers must decide Oxford or no Oxford and not switch back and forth, except when omitting the Oxford comma could cause confusion as in the cheese and crackers example. Rule 2. Use a comma to separate two adjectives when the adjectives are interchangeable. Example: He is a strong, healthy man. Example: We stayed at an expensive summer resort. Rule 3a. Many inexperienced writers run two independent clauses together by using a comma instead of a period. This results in the dreaded run-on sentence or, more technically, a comma splice. Incorrect: He walked all the way home, he shut the door. There are several simple remedies: Correct: He walked all the way home. He shut the door. Correct: After he walked all the way home, he shut the door. Correct: He walked all the way home, and he shut the door. Rule 3b. In sentences where two independent clauses are joined by connectors such as and, or, but, etc., put a comma at the end of the first clause. Incorrect: He walked all the way home and he shut the door. Correct: He walked all the way home, and he shut the door. Some writers omit the comma if the clauses are both quite short: Example: I paint and he writes. Rule 3c. If the subject does not appear in front of the second verb, a comma is generally unnecessary. Example: He thought quickly but still did not answer correctly. Rule 4a. Use a comma after certain words that introduce a sentence, such as well, yes, why, hello, hey, etc. Examples: Rule 4b. Use commas to set off expressions that interrupt the sentence flow (nevertheless, after all, by the way, on the other hand, however, etc.). Example: I am, by the way, very nervous about this. Rule 5. Use commas to set off the name, nickname, term of endearment, or title of a person directly addressed. Examples: Rule 6. Use a comma to separate the day of the month from the year, and—what most people forget!—always put one after the year, also. Example: It was in the Sun's June 5, 2003, edition. No comma is necessary for just the month and year. Example: It was in a June 2003 article. Rule 7. Use a comma to separate a city from its state, and remember to put one after the state, also. Example: I'm from the Akron, Ohio, area. Rule 8. Traditionally, if a person's name is followed by Sr. or Jr., a comma follows the last name: Martin Luther King, Jr. This comma is no longer considered mandatory. However, if a comma does precede Sr. or Jr., another comma must follow the entire name when it appears midsentence. Correct: Al Mooney Sr. is here. Correct: Al Mooney, Sr., is here. Incorrect: Al Mooney, Sr. is here. Rule 9. Similarly, use commas to enclose degrees or titles used with names. Example: Al Mooney, M.D., is here. Rule 10. When starting a sentence with a dependent clause, use a comma after it. Example: If you are not sure about this, let me know now. But often a comma is unnecessary when the sentence starts with an independent clause followed by a dependent clause. Example: Let me know now if you are not sure about this. Rule 11. Use commas to set off nonessential words, clauses, and phrases (see the "Who, That, Which" section in Chapter One, Rule 2b). Incorrect: Jill who is my sister shut the door. Correct: Jill, who is my sister, shut the door. Incorrect: The man knowing it was late hurried home. Correct: The man, knowing it was late, hurried home. In the preceding examples, note the comma after sister and late. Nonessential words, clauses, and phrases that occur midsentence must be enclosed by commas. The closing comma is called an appositive comma. Many writers forget to add this important comma. Following are two instances of the need for an appositive comma with one or more nouns. Incorrect: My best friend, Joe arrived. Correct: My best friend, Joe, arrived. Incorrect: The three items, a book, a pen, and paper were on the table. Correct: The three items, a book, a pen, and paper, were on the table. Rule 12. If something or someone is sufficiently identified, the description that follows is considered nonessential and should be surrounded by commas. Examples: This leads to a persistent problem. Look at the following sentence: Example: My brother Bill is here. Now, see how adding two commas changes that sentence's meaning: Example: My brother, Bill, is here. Careful writers and readers understand that the first sentence means I have more than one brother. The commas in the second sentence mean that Bill is my only brother. Why? In the first sentence, Bill is essential information: it identifies which of my two (or more) brothers I'm speaking of. This is why no commas enclose Bill. In the second sentence, Bill is nonessential information—whom else but Bill could I mean?—hence the commas. Comma misuse is nothing to take lightly. It can lead to a train wreck like this: Example: Mark Twain's book, Tom Sawyer, is a delight. Because of the commas, that sentence states that Twain wrote only one book. In fact, he wrote more than two dozen of them. Rule 13a. Use commas to introduce or interrupt direct quotations. Examples: This rule is optional with one-word quotations. Example: He said "Stop." Rule 13b. If the quotation comes before he said, she wrote, they reported, Dana insisted, or a similar attribution, end the quoted material with a comma, even if it is only one word. Examples: Rule 14. Use a comma to separate a statement from a question. Example: I can go, can't I? Rule 15. Use a comma to separate contrasting parts of a sentence. Example: That is my money, not yours. Rule 16a. Use a comma before and after certain introductory words or terms, such as namely, that is, i.e., e.g., and for instance, when they are followed by a series of items. Example: You may be required to bring many items, e.g., sleeping bags, pans, and warm clothing. Rule 16a. Commas should precede the term etc. and enclose it if it is placed midsentence. Example: Sleeping bags, pans, warm clothing, etc., are in the tent. |

Dashes

|

Dashes, like commas, semicolons, colons, ellipses, and parentheses, indicate added emphasis, an interruption, or an abrupt change of thought. Experienced writers know that these marks are not interchangeable. Note how dashes subtly change the tone of the following sentences: Examples: Rule 1. Words and phrases between dashes are not generally part of the subject. Example: Joe—and his trusty mutt—was always welcome. Rule 2. Dashes replace otherwise mandatory punctuation, such as the commas after Iowa and 2013 in the following examples: Without dash: The man from Ames, Iowa, arrived. With dash: The man—he was from Ames, Iowa—arrived. Without dash: The May 1, 2013, edition of the Ames Sentinel arrived in June. With dash: The Ames Sentinel—dated May 1, 2013—arrived in June. Rule 3. Some writers and publishers prefer spaces around dashes. Example: Joe — and his trusty mutt — was always welcome. |

Ellipsis Marks

|

An ellipsis (plural: ellipses) is a punctuation mark consisting of three dots. Use an ellipsis when omitting a word, phrase, line, paragraph, or more from a quoted passage. Ellipses save space or remove material that is less relevant. They are useful in getting right to the point without delay or distraction: Full quotation: "Today, after hours of careful thought, we vetoed the bill." With ellipsis: "Today…we vetoed the bill." Although ellipses are used in many ways, the three-dot method is the simplest. Newspapers, magazines, and books of fiction and nonfiction use various approaches that they find suitable. Some writers and editors feel that no spaces are necessary. Example: I don't know…I'm not sure. Others enclose the ellipsis with a space on each side. Example: I don't know … I'm not sure. Still others put a space either directly before or directly after the ellipsis. Examples: A four-dot method and an even more rigorous method used in legal works require fuller explanations that can be found in other reference books. Rule 1. Many writers use an ellipsis whether the omission occurs at the beginning of a sentence, in the middle of a sentence, or between sentences. A common way to delete the beginning of a sentence is to follow the opening quotation mark with an ellipsis, plus a bracketed capital letter: Example: "…[A]fter hours of careful thought, we vetoed the bill." Other writers omit the ellipsis in such cases, feeling the bracketed capital letter gets the point across. For more on brackets, see "Parentheses and Brackets." Rule 2. Ellipses can express hesitation, changes of mood, suspense, or thoughts trailing off. Writers also use ellipses to indicate a pause or wavering in an otherwise straightforward sentence. Examples: |

Exclamation Points

|

Rule 1. Use an exclamation point to show emotion, emphasis, or surprise. Examples: Rule 2. An exclamation point replaces a period at the end of a sentence. Incorrect: I'm truly shocked by your behavior!. Rule 3. Do not use an exclamation point in formal business writing. Rule 4. Overuse of exclamation points is a sign of undisciplined writing. Do not use even one of these marks unless you're convinced it is justified. |

Hyphens

|

There are two commandments about this misunderstood punctuation mark. First, hyphens must never be used interchangeably with dashes (see the "Dashes" section), which are noticeably longer. Second, there should never be spaces around hyphens. Incorrect: 300—325 people Incorrect: 300 - 325 people Correct: 300-325 people Hyphens' main purpose is to glue words together. They notify the reader that two or more elements in a sentence are linked. Although there are rules and customs governing hyphens, there are also situations when writers must decide whether to add them for clarity. Hyphens Between WordsRule 1. Generally, hyphenate two or more words when they come before a noun they modify and act as a single idea. This is called a compound adjective. Examples: When a compound adjective follows a noun, a hyphen may or may not be necessary. Example: The apartment is off campus. However, some established compound adjectives are always hyphenated. Double-check with a dictionary or online. Example: The design is state-of-the-art. Rule 2a. A hyphen is frequently required when forming original compound verbs for vivid writing, humor, or special situations. Examples: Rule 2b. When writing out new, original, or unusual compound nouns, writers should hyphenate whenever doing so avoids confusion. Examples: Writers using familiar compound verbs and nouns should consult a dictionary or look online to decide if these verbs and nouns should be hyphenated. Rule 3. An often overlooked rule for hyphens: The adverb very and adverbs ending in -ly are not hyphenated. Incorrect: the very-elegant watch Incorrect: the finely-tuned watch This rule applies only to adverbs. The following two sentences are correct because the -ly words are adjectives rather than adverbs: Correct: the friendly-looking dog Correct: a family-owned cafe Rule 4. Hyphens are often used to tell the ages of people and things. A handy rule, whether writing about years, months, or any other period of time, is to use hyphens unless the period of time (years, months, weeks, days) is written in plural form: With hyphens: No hyphens: The child is two years old. (Because years is plural.) Exception: The child is one year old. (Or day, week, month, etc.) Note that when hyphens are involved in expressing ages, two hyphens are required. Many writers forget the second hyphen: Incorrect: We have a two-year old child. Without the second hyphen, the sentence is about an "old child." Rule 5. Never hesitate to add a hyphen if it solves a possible problem. Following are two examples of well-advised hyphens: Confusing: I have a few more important things to do. With hyphen: I have a few more-important things to do. Without the hyphen, it's impossible to tell whether the sentence is about a few things that are more important or a few more things that are all equally important. Confusing: He returned the stolen vehicle report. With hyphen: He returned the stolen-vehicle report. With no hyphen, we could only guess: Was the vehicle report stolen, or was it a report on stolen vehicles? Rule 6. When using numbers, hyphenate spans or estimates of time, distance, or other quantities. Remember not to use spaces around hyphens. Examples: Rule 7. Hyphenate all compound numbers from twenty-one through ninety-nine. Examples: Rule 8. Hyphenate all spelled-out fractions. Example: more than two-thirds of registered voters Rule 9. Hyphenate most double last names. Example: Sir Winthrop Heinz-Eakins will attend. Rule 10. As important as hyphens are to clear writing, they can become an annoyance if overused. Avoid adding hyphens when the meaning is clear. Many phrases are so familiar (e.g., high school, twentieth century, one hundred percent) that they can go before a noun without risk of confusing the reader. Examples: Rule 11. When in doubt, look it up. Some familiar phrases may require hyphens. For instance, is a book up to date or up-to-date? Don't guess; have a dictionary close by, or look it up online. Hyphens with Prefixes and SuffixesA prefix (a-, un-, de-, ab-, sub-, post-, anti-, etc.) is a letter or set of letters placed before a root word. The word prefix itself contains the prefix pre-. Prefixes expand or change a word's meaning, sometimes radically: the prefixes a-, un-, and dis-, for example, change words into their opposites (e.g., political, apolitical; friendly, unfriendly; honor, dishonor). Rule 1. Hyphenate prefixes when they come before proper nouns or proper adjectives. Examples: Rule 2. For clarity, many writers hyphenate prefixes ending in a vowel when the root word begins with the same letter. Example: Rule 3. Hyphenate all words beginning with the prefixes self-, ex- (i.e., former), and all-. Examples: Rule 4. Use a hyphen with the prefix re- when omitting the hyphen would cause confusion with another word. Examples: Rule 5. Writers often hyphenate prefixes when they feel a word might be distracting or confusing without the hyphen. Examples: A suffix (-y, -er, -ism, -able, etc.) is a letter or set of letters that follows a root word. Suffixes form new words or alter the original word to perform a different task. For example, the noun scandal can be made into the adjective scandalous by adding the suffix -ous. It becomes the verb scandalize by adding the suffix -ize. Rule 1. Suffixes are not usually hyphenated. Some exceptions: -style, -elect, -free, -based. Examples: Rule 2. For clarity, writers often hyphenate when the last letter in the root word is the same as the first letter in the suffix. Examples: Rule 3. Use discretion—and sometimes a dictionary—before deciding to place a hyphen before a suffix. But do not hesitate to hyphenate a rare usage if it avoids confusion. Examples: Although the preceding hyphens help clarify unusual terms, they are optional and might not be every writer's choice. Still, many readers would scratch their heads for a moment over danceathon and eelesque. |

Parentheses and Brackets

|

Parentheses and brackets must never be used interchangeably. Parentheses

Brackets

Periods

Question Marks

Quotation Marks

Semicolons

|