What causes nausea and vomiting?

|

Brain & central nervous system (nervous system) Cardiovascular Endocrine Gastrointestinal Genitourinary Functional/Psychiatric

Noxious Chemicals (via area postrema) Increased Intracranial Pressure Mass Fluid Inflammation Rapid Osmolality Shifts Vestibular disorders Central Vertigo Cardiovascular Endocrine Pregnancy Gastrointestinal Structural Mechanical obstruction Delayed emptying/peristalsis Inflammatory Gastroenteritis Esophagitis Gastritis Hepatitis Genitourinary Functional/Psychiatric |

Alphabetical

Neurological causes of nausea and vomiting Nausea and vomitnig caused by drug side effects Vomiting in infants |

How is the cause of nausea and vomiting diagnosed?

|

Diagnosis often can be made when the health care professional takes a careful history and performs a physical examination. Any tests that need to be ordered will be based on the information from the history and physical exam, and sometimes no further testing is required to make the diagnosis. Laboratory tests and X-rays may be ordered to assess the stability of the patient and not necessarily to make the diagnosis. For example, a patient with food poisoning may need blood tests ordered to measure the electrolytes(minerals) and other chemicals, since the patient may lose significant amounts of sodium, potassium, and chloride from the body from persistent vomiting and diarrhea. Urinalysis may be helpful in assessing hydration status. Concentrated, dark urine is associated with dehydration because the kidneys try to preserve as much water as possible in the body. Ketones in the urine are also a sign of dehydration. What treatments and drugs help relieve nausea or vomiting? Nausea and vomiting can be treated with medication at the same time as the search for the underlying diagnosis are being carried out. Ideally, these symptoms should resolve when the underlying illness is treated and controlled. Nausea and vomiting are often made worse when you are dehydrated, resulting in a vicious cycle. Nausea makes it difficult to drink fluid, making the dehydration worse, which then increases nausea. Intravenous fluids may be provided to correct this issue and break the cycle. There are varieties of anti-nausea medications (antiemetics) that your doctor may prescribe. These drugs can be administered in different ways depending upon your ability to take them. Medications are available by pill, liquid, or tablets that dissolve on or under the tongue, by intravenous or intramuscular injection, or by rectal suppository. Common medications used to control nausea and vomiting include: •promethazine (Phenergan), •prochlorperazine (Compazine), •droperidol (Inapsine) •metoclopramide (Reglan), and •ondansetron (Zofran). The decision as to which medication to use will depend on the patient's condition. What natural home remedies help relieve nausea and vomiting? It is important to rest the stomach and yet still avoid dehydration. Clear fluids should be attempted for the first 24 hours of an illness, and then the diet should be advanced as tolerated. Clear fluids are easy for the stomach to absorb and include: •Water •Sports drinks •Clear broths •Popsicles Prediction and prevention Predicting when you might vomit Before you vomit, you may begin to feel nauseous. Nausea can be described as stomach discomfort and the sensation of your stomach churning. Young children may not be able to recognize nausea, but they may complain of a stomachache before they vomit. v Prevention When you begin feeling nauseous, there are a few steps you can take to potentially stop yourself from actually vomiting. The following tips may help prevent vomiting before it starts: Take deep breaths. Drink ginger tea or eat fresh or candied ginger. Take an OTC medication to stop vomiting, such as Pepto-Bismol. If you’re prone to motion sickness, take an If you’re prone to indigestion or acid reflux, avoid oily or spicy foods. Sit down or lie down with your head and back propped up. Vomiting caused by certain conditions may not always be possible to prevent. For example, consuming enough alcohol to cause a toxic level in your bloodstream will result in vomiting as your body attempts to return to a non-toxic level. Care and recovery after vomiting Drinking plenty of water and other liquids to replenish lost fluids is important after a bout of vomiting. Start slowly by sipping water or sucking on ice chips, then add in more clear liquids like sports drinks or juice. You can make your own rehydration solution using: 1/2 teaspoon salt 6 teaspoons sugar 1 liter water You shouldn’t have a big meal after you vomit. Begin with saltine crackers or plain rice or bread. You should also avoid foods that are difficult to digest, like: milk cheese caffeine fatty or fried foods spicy food After you vomit, you should rinse your mouth with cool water to remove any stomach acid that could damage your teeth. Don’t brush your teeth right after vomiting as this could cause damage to the already weakened enamel. |

Treatment

How to treat vomiting

|

1. Treatment at home. 2. Treatment in a hospital. The Vomiting Patient in the ED: Evaluation and Management 1. Treatment at home. Treatment for vomiting depends on the underlying cause. Drinking plenty of water and sports drinks containing electrolytes can help prevent dehydration. In adults Consider these home remedies: Eat small meals consisting of only light and plain foods (rice, bread, crackers or the BRAT diet). Sip clear liquids. Rest and avoid physical activity. Medications can be helpful: Over-the-counter (OTC) medications like Imodium and Pepto-Bismol may help suppress nausea and vomiting as you wait for your body to fight off an infection Depending on the cause, a doctor may prescribe antiemetic drugs, like ondansetron (Zofran), granisetron, or promethazine. OTC antacids or other prescription medications can help treat the symptoms of acid reflux. Anti-anxiety medications can be prescribed if your vomiting is related to an anxiety condition. In babies Keep your baby lying on their stomach or side to lessen the chances of inhaling vomit Make sure your baby consumes extra fluids, such as water, sugar water, oral rehydration solutions (Pedialyte) or gelatin; if your baby is still breastfeeding, continue to breastfeed often. Avoid solid foods. See a doctor if your baby refuses to eat or drink anything for more than a few hours. When pregnant Pregnant women who have morning sickness or hyperemesis gravidarum may need to receive intravenous fluids if they’re unable to keep down any fluids. More severe cases of hyperemesis gravidarum might require total parenteral nutrition given through an IV. v A doctor may also prescribe antiemetics, such as promethazine, metoclopramide (Reglan), or droperidol (Inapsine), to help prevent nausea and vomiting. These medications can be given by mouth, IV, or suppository When to see a doctor Adults and babies Adults and babies should see a doctor if they: are vomiting repeatedly for more than a day are unable to keep down any fluids have green colored vomit or the vomit contains blood have signs of severe dehydration, such as fatigue, dry mouth, excessive thirst, sunken eyes, fast heart rate, and little or no urine; in babies, signs of severe dehydration also include crying without producing tears and drowsiness have lost significant weight since the vomiting began are vomiting off and on for over a month Pregnant women Pregnant women should see a doctor if their nausea and vomiting makes it impossible to eat or drink or keep anything in the stomach. What is the definition of antiemetics? How do antiemetic medicines work? How do you safely take OTC antiemetic medicines? How can you safely store OTC antiemetic medicines? Who shouldn’t take OTC antiemetic medicines? Can OTC antiemetic medicines cause problems with any other medicines I take? Questions to ask your doctor •What kind of antiemetic medicine is best for me? •How does the medicine help my nausea? •How often can I take it? •Is there a limit on how many days I can take it? •What kinds of side effects should I look for? Medical emergencies Vomiting accompanied by the following symptoms should be treated as a medical emergency: severe chest pain sudden and severe headache shortness of breath blurred vision sudden stomach pain stiff neck and high fever blood in the vomit Infants younger than 3 months who have a rectal fever of 100.4ºF (38ºC) or higher, with or without vomiting, should see a doctor. |

2. The Vomiting Patient in the ED: Evaluation and Management

Metoclopramide

| Antiemetics |

|

Metoclopramide Oral/ IV / IM (Reglan®) What is metoclopramide? In 2012, metoclopramide was one of the top 100 most prescribed medications in the United States. Metoclopramide is a medication used mostly for stomach and esophageal problems. It is commonly used to treat and prevent nausea and vomiting, to help with emptying of the stomach in people with delayed stomach emptying, and to help with gastroesophageal reflux disease. It is also used to treat migraine headaches. Antiemetic and Gut motility stimulator How should you use metoclopramide? Usual Adult Dose for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Oral: 10 to 15 mg up to 4 times a day 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, depending upon symptoms being treated and clinical response. Therapy should not exceed 12 weeks. Usual Adult Dose for Small Intestine Intubation: If the tube has not passed the pylorus with conventional methods in 10 minutes, a single (undiluted) dose may be administered IV slowly over 1 to 2 minutes: Adults and pediatric patients greater than or equal to 14 years: 10 mg IV as a single dose administered over 1 to 2 minutes. Usual Adult Dose for Radiographic Exam: Adults and pediatric patients greater than or equal to 14 years: 10 mg IV as a single dose administered over 1 to 2 minutes to facilitate gastric emptying where delayed gastric emptying interferes with radiological examination of the stomach and/or small intestine. Usual Adult Dose for Gastroparesis: During the earliest manifestations of diabetic gastric stasis, oral administration may be initiated. If severe symptoms are present, therapy should begin with IM or IV administration for up to 10 days until symptoms subside at which time the patient can be switched to oral therapy. Since diabetic gastric stasis is often recurrent, therapy should be reinstituted at the earliest manifestation. Parenteral: 10 mg 4 times daily, IV (slowly over a 1 to 2 minute period) or IM for up to 10 days. Oral: 10 mg 4 times daily, 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, for 2 to 8 weeks depending on clinical response. Usual Adult Dose for Nausea/Vomiting -- Chemotherapy Induced: IV infusion: 1 to 2 mg/kg/dose (depending on the emetogenic potential of the agent) IV (infused over a period of not less than 15 minutes) 30 minutes before administration of chemotherapy. The dose may be repeated twice at 2 hour intervals following the initial dose. If vomiting is still not suppressed, the same dose may be repeated 3 more times at 3 hour intervals. For doses higher than 10 mg, the injection should be diluted in 50 mL of a parenteral solution. Normal saline is the preferred diluent. If acute dystonic reactions occur, 50 mg of diphenhydramine hydrochloride may be injected IM. Usual Adult Dose for Migraine: Use for treatment of migraine headaches is not an FDA approved indication; however, metoclopramide has shown efficacy in studies at a dose of 10 to 20 mg IV once (used in combination with analgesics or ergot derivatives). Usual Pediatric Dose for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Metoclopramide is not approved by the FDA for gastroesophageal reflux disease in pediatric patients; however, the following doses have been studied: Oral, IM, IV: Infants and Children: 0.4 to 0.8 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses Usual Pediatric Dose for Small Intestine Intubation: Metoclopramide IV is approved by the FDA for pediatric use to facilitate small bowel intubation by causing gastric emptying where delayed gastric emptying interferes with radiological examination of the stomach and/or small intestine. If the tube has not passed the pylorus with conventional methods in 10 minutes, a single (undiluted) dose may be administered IV slowly over 1 to 2 minutes: Less than 6 years: 0.1 mg/kg IV as a single dose 6 to 14 years: 2.5 to 5 mg IV as a single dose Children greater than 14 years: 10 mg as a single dose Usual Pediatric Dose for Nausea/Vomiting -- Chemotherapy Induced: Metoclopramide is not approved by the FDA for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients; however, the following doses have been studied: IV: 1 to 2 mg/kg/dose IV every 30 minutes before chemotherapy and every 2 to 4 hours Usual Pediatric Dose for Nausea/Vomiting -- Postoperative: Metoclopramide is not approved by the FDA for postoperative nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients; however, the following doses have been studied: IV: Children less than or equal to 14 years: 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg/dose (maximum dose: 10 mg/dose); repeat every 6 to 8 hours as needed Children greater than 14 years and Adults: 10 mg; repeat every 6 to 8 hours as needed Usual Adult Dose for Nausea/Vomiting: Postoperative nausea and vomiting: Parenteral: 10 to 20 mg IM at or near the end of surgery Why is this medication prescribed? This medication works by blocking dopamine and serotonin from stimulating this chemoreceptor trigger zone, which helps prevent and treat nausea and vomiting. This medication can also be used to treat gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) and diabetic gastroparesis by helping the gastrointestinal (GI) tract’s motility and by making gastric emptying faster. Metoclopramide is in a class of medications called prokinetic agents. It works by speeding the movement of food through the stomach and intestines. How to Take Metoclopramide (Reglan®) The oral form of metoclopramide may be taken as a scheduled or as-needed medication. If you are taking a scheduled dose, it should be taken 30 minutes before a meal and again at bedtime. The intravenous form of metoclopramide may be given prior to a chemotherapy regimen or as needed as an IV push (depending on the dose) or as a short infusion. This medication can also be given as an intramuscular (IM, into a muscle) injection if your provider feels this is necessary. How should this medicine be used? Metoclopramide comes as a tablet, an orally disintegrating (dissolving) tablet, and a solution (liquid) to take by mouth. It is usually taken 4 times a day on an empty stomach, 30 minutes before each meal and at bedtime. When metoclopramide is used to treat symptoms of GERD, it may be taken less frequently, especially if symptoms only occur at certain times of day. Follow the directions on your prescription label carefully, and ask your doctor or pharmacist to explain any part you do not understand. Take metoclopramide exactly as directed. Do not take more or less of it or take it more often than prescribed by your doctor. If you are taking the orally disintegrating tablet, use dry hands to remove the tablet from the package just before you take your dose. If the tablet breaks or crumbles, dispose of it and remove a new tablet from the package. Gently remove the tablet and immediately place it on the top of your tongue. The tablet will usually dissolve in about one minute and can be swallowed with saliva. If you are taking metoclopramide to treat the symptoms of slow stomach emptying caused by diabetes, you should know that your symptoms will not improve all at once. You may notice that your nausea improves early in your treatment and continues to improve over the next 3 weeks. Your vomiting and loss of appetite may also improve early in your treatment, but it may take longer for your feeling of fullness to go away. Continue to take metoclopramide even if you feel well. Do not stop taking metoclopramide without talking to your doctor. You may experience withdrawal symptoms such as dizziness, nervousness, and headaches when you stop taking metoclopramide. Other uses for this medicine Metoclopramide is also sometimes used to treat the symptoms of slowed stomach emptying in people who are recovering from certain types of surgery, and to prevent nausea and vomiting in people who are being treated with chemotherapy for cancer. Ask your doctor about the risks of using this medication to treat your condition. This medication may be prescribed for other uses; ask your doctor or pharmacist for more information. What special precautions should I follow? Before taking metoclopramide, •tell your doctor and pharmacist if you are allergic to metoclopramide, any other medications, or any of the ingredients in metoclopramide tablets or solution. Ask your doctor or pharmacist or check the Medication Guide for a list of the ingredients. •tell your doctor and pharmacist what prescription and nonprescription medications, vitamins, nutritional supplements and herbal products you are taking or plan to take. Be sure to mention any of the following: acetaminophen (Tylenol, others); antihistamines; aspirin; atropine (in Lonox, in Lomotil); cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune); barbiturates such as pentobarbital (Nembutal), phenobarbital (Luminal), and secobarbital (Seconal); digoxin (Lanoxicaps, Lanoxin); haloperidol (Haldol);insulin; ipratropium (Atrovent); lithium (Eskalith, Lithobid); levodopa (in Sinemet, in Stalevo); medications for anxiety, blood pressure, irritable bowel disease, motion sickness, nausea, Parkinson's disease, ulcers, or urinary problems; monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, including isocarboxazid (Marplan), phenelzine (Nardil), selegiline (Eldepryl, Emsam, Zelapar), and tranylcypromine (Parnate); narcotic medications for pain; sedatives; sleeping pills; tetracycline (Bristacycline, Sumycin); or tranquilizers. Your doctor may need to change the doses of your medications or monitor you more carefully for side effects. •tell your doctor if you have or have ever had blockage, bleeding, or a tear in your stomach or intestines; pheochromocytoma (tumor on a small gland near the kidneys); or seizures. Your doctor will probably tell you not to take metoclopramide. •tell your doctor if you have or have ever had Parkinson's disease (PD; a disorder of the nervous system that causes difficulties with movement, muscle control, and balance); high blood pressure; depression; breast cancer; asthma;glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6PD) deficiency (an inherited blood disorder); NADH cytochrome B5 reductase deficiency (an inherited blood disorder); or heart, liver, or kidney disease. •tell your doctor if you are pregnant, plan to become pregnant, or are breastfeeding. If you become pregnant while taking metoclopramide, call your doctor. •talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of taking metoclopramide if you are 65 years of age or older. Older adults should not usually take metoclopramide, unless it is used to treat slow stomach emptying, because it is not as safe or effective as other medications that can be used to treat those conditions. •if you are having surgery, including dental surgery, tell the doctor or dentist that you are taking metoclopramide. •you should know that this medication may make you drowsy. Do not drive a car or operate machinery until you know how this medication affects you. •ask your doctor about the safe use of alcohol while you are taking this medication. Alcohol can make the side effects of metoclopramide worse. What special dietary instructions should I follow? Unless your doctor tells you otherwise, continue your regular diet. What should you do if you forget a dose? Take the missed dose as soon as you remember it. However, if it is almost time for the next dose, skip the missed dose and continue your regular dosing schedule. Do not take a double dose to make up for a missed one. What side effects can this medication cause? Metoclopramide may cause side effects. Tell your doctor if any of these symptoms are severe or do not go away: •drowsiness •excessive tiredness •weakness •headache •dizziness •diarrhea •nausea •vomiting •breast enlargement or discharge •missed menstrual period •decreased sexual ability •frequent urination •inability to control urination Some side effects can be serious. If you experience any of the following symptoms, or those mentioned in the IMPORTANT WARNING section, call your doctor immediately: •tightening of the muscles, especially in the jaw or neck •speech problems •depression •thinking about harming or killing yourself •fever •muscle stiffness •confusion •fast, slow, or irregular heartbeat •sweating •restlessness •nervousness or jitteriness •agitation •difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep •pacing •foot tapping •slow or stiff movements •blank facial expression •uncontrollable shaking of a part of the body •difficulty keeping your balance •rash •hives •swelling of the eyes, face, lips, tongue, mouth, throat, arms, hands, feet, ankles, or lower legs •sudden weight gain •difficulty breathing or swallowing •high-pitched sounds while breathing •vision problems Metoclopramide may cause other side effects. Call your doctor if you have any unusual problems while you are taking this medication. If you experience a serious side effect, you or your doctor may send a report to the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program online (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch) or by phone (1-800-332-1088). What should you know about storage and disposal of this medication? Keep this medication in the container it came in, tightly closed, and out of reach of children. Store it at room temperature and away from excess heat and moisture (not in the bathroom). It is important to keep all medication out of sight and reach of children as many containers (such as weekly pill minders and those for eye drops, creams, patches, and inhalers) are not child-resistant and young children can open them easily. To protect young children from poisoning, always lock safety caps and immediately place the medication in a safe location – one that is up and away and out of their sight and reach. http://www.upandaway.org Unneeded medications should be disposed of in special ways to ensure that pets, children, and other people cannot consume them. However, you should not flush this medication down the toilet. Instead, the best way to dispose of your medication is through a medicine take-back program. Talk to your pharmacist or contact your local garbage/recycling department to learn about take-back programs in your community. See the FDA's Safe Disposal of Medicines website (http://goo.gl/c4Rm4p) for more information if you do not have access to a take-back program. In case of emergency/overdose In case of overdose, call the poison control helpline at 1-800-222-1222. Information is also available online at https://www.poisonhelp.org/help. If the victim has collapsed, had a seizure, has trouble breathing, or can't be awakened, immediately call emergency services at 911. Symptoms of overdose may include the following: •drowsiness •confusion •seizures •unusual, uncontrollable movements •lack of energy •bluish coloring of the skin •headache •shortness of breath What other information should you know? Keep all appointments with your doctor. Do not let anyone else take your medication. Ask your pharmacist any questions you have about refilling your prescription. It is important for you to keep a written list of all of the prescription and nonprescription (over-the-counter) medicines you are taking, as well as any products such as vitamins, minerals, or other dietary supplements. You should bring this list with you each time you visit a doctor or if you are admitted to a hospital. It is also important information to carry with you in case of emergencies. Brand names •Clopra®¶ •Maxolon®¶ •Metozolv® ODT •Reglan® |

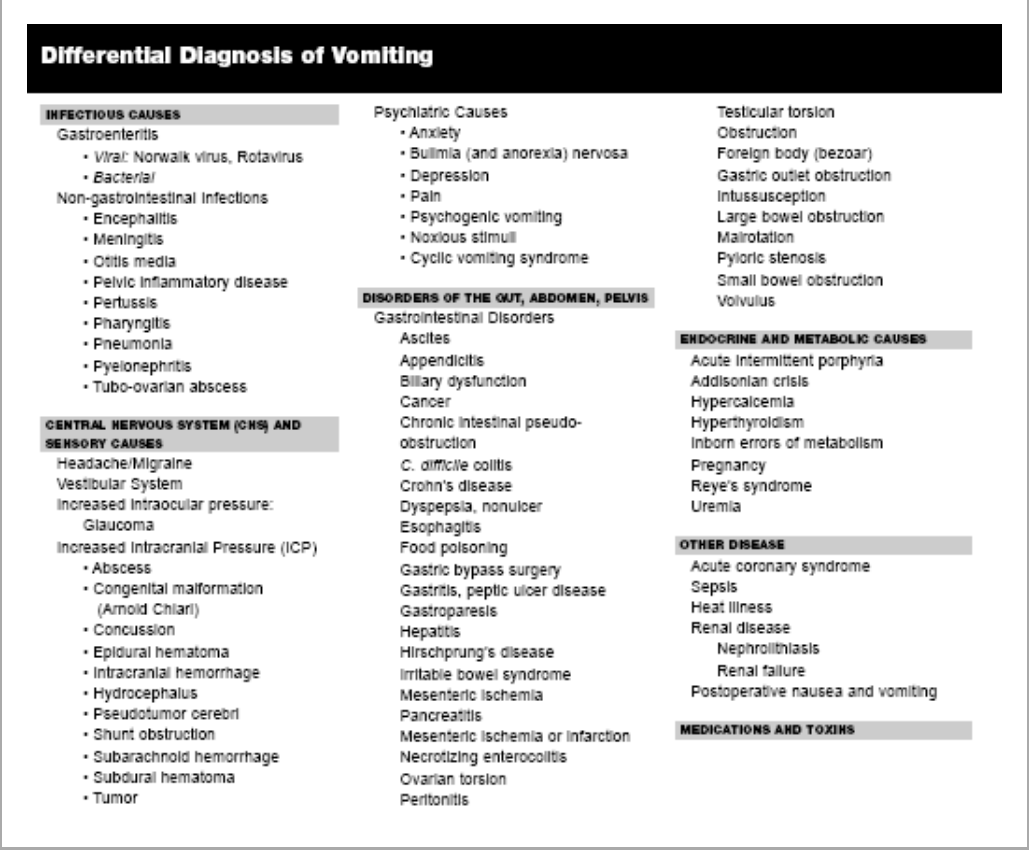

Few sounds or smells in the emergency department (ED) get our attention as easily as vomiting. In response, we might reflexively order our "one-size-fits-all" standard antiemetic and begin by assuming that this is probably just another case of "gastroenteritis." There are, however, several antiemetics to choose from, each with its own advantages and disadvantages, as well as a myriad of diagnostic possibilities to consider. (See Table 1.) In evaluating and treating the vomiting patient, the emergency physician should discern the correct diagnosis from the multitude of potential causes, exclude the serious and potentially life-threatening conditions (see Table 2), identify potential complications of persistent or severe vomiting, assess and treat dehydration, and carefully consider therapeutic options of nasogastric (NG) suctioning, intravenous (IV) hydration, and antiemetic medication.

Pathophysiology There are three basic phases of vomiting. Nausea is the unpleasant sensation that immediately precedes vomiting, and is typically associated with hypersalivation and tachycardia. Retching, the second phase, occurs when the pylorus contracts while the fundus relaxes, allowing contents to move toward the gastric cardia. Finally, emesis occurs with the forceful contraction of the abdominal muscles and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, causing retrograde movement of the gastric contents from the stomach out the mouth. In contrast, regurgitation is the involuntary return of esophageal contents to the hypopharynx without preceding nausea and little abdominal muscular effort. The numerous signals necessary to coordinate the act of vomiting are processed by several brainstem nuclei in the reticular formation of the medulla and pons, together called the emesis center, which receives input from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) of the area postrema of the fourth ventricle, the autonomic afferent nerves (especially the vagus) from the gastrointestinal tract, the labyrinthine system, and the cerebral cortex (vision, smell, taste). Vomiting is a potentially protective mechanism, emptying the stomach to eliminate toxins, and decrease volume and minimize luminal pressures in obstructions. When persistent or severe, however, vomiting can become more than a nuisance and can lead to various complications. (See Table 3.)

Clinical Approach to the Vomiting Patient History. There are five aspects to the history that help narrow the differential from the long list of causes (see Table 1): age, duration, frequency and timing, characteristics of the vomitus, and associated symptoms. Bilious vomiting in a neonate is an ominous sign and should prompt an evaluation with contrast (barium) swallow radiographs to evaluate for malrotation with or without volvulus, intestinal atresia or intestinal stenosis. Nonbilious vomiting in a neonate could indicate hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS), intestinal atresia, or an obstructing lesion (web, band) proximal to the ampulla of Vater. In early infancy, inborn errors of metabolism can manifest with vomiting, seizures, hypotonia or hypertonia, and lethargy or coma. Metabolic acidosis, ketosis, elevated ammonia or hypoglycemia may be clues to these disorders of carbohydrate metabolism (such as glycogen storage), amino acid or organic acid defects (such as phenylketonuria), lysosomal storage, peroxisomes, or fatty acid oxidation. Food sensitivity is common, affecting up to 3-5% of bottle-fed infants.1 Infants and small children are most likely to have simple gastroenteritis, otitis, urinary tract infection or pharyngitis, but are also at risk for intussusception. Adolescents with vomiting might have appendicitis, and young women should be suspected of pregnancy or pyelonephritis. In contrast, the elderly are more likely to have mesenteric infarction, cancer, volvulus, Addison's disease, Ménière's disease, glaucoma, subdural hematoma, or uremia. Symptom duration is helpful because the differential diagnoses differ significantly for acute and chronic symptoms. Acute vomiting (less than one month in duration) tends to be more worrisome and is more frequently seen in the ED. Chronic vomiting occurs over a period greater than one month and is usually less common. Rapidity of symptom onset is also helpful. An abrupt onset of nausea and vomiting might suggest gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, food poisoning, or a drug-related side-effect. A more insidious onset is suggestive of reflux, gastroparesis, medications, metabolic disorders, or pregnancy. Timing and frequency is also of particular importance. The vomiting may be directly associated with meals or may occur continuously, either irregularly or at predictable times. Think of an ingested bacterial toxin for acute vomiting 2-6 hours after eating, as seen with Staphylococcus aureus or Bacillus cereus. Vomiting that is precipitated by meals suggests psychogenic vomiting, pyloric channel ulcer, gastritis, biliary disease, or pancreatitis. Chronic vomiting within one hour of ingestion is consistent with gastric or proximal small bowel obstruction, which can include peptic ulcer, neoplasm, and, less commonly, superior mesenteric artery syndrome or gastric volvulus. If the onset is delayed greater than one hour after eating, gastroparesis and distal bowel obstruction should be of concern. Vomiting that occurs in the early morning upon awakening points toward alcoholic binge, early pregnancy, increased intracranial pressure (ICP), or metabolic disturbances such as uremia or Addison's disease. If a psychological reason is suspected, conversion disorders tend to present with continuous vomiting, while vomiting associated with major depression tend to present with either habitual postprandial or irregular vomiting. A psychological etiology should be a diagnosis of exclusion in the patient with chronic unexplained vomiting only after thorough work-up, and usually is not made by the emergency physician. The character of the vomitus is the fourth key portion of the history. Is the vomitus bloody, bilious, nonbilious, feculant, or projectile? Hematemesis or coffee ground emesis is suggestive of peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss tear, esophageal varices, or malignancy. Regurgitation of undigested food is suggestive of esophageal disorders such as achalasia, esophageal stricture, bolus impaction, hiatal hernia, or Zenker's diverticulum. Non-bilious emesis and partially digested food signifies gastritis, gastroparesis, or gastric outlet obstruction as seen in patients with pyloric strictures secondary to peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and infants with HPS. Bilious vomiting, on the other hand, excludes gastric outlet obstruction and can signify small bowel obstruction. Feculant vomiting reflects bacterial degradation of stagnant intestinal contents and is associated with distal small or large bowel obstruction. This can also be seen with blind-loop syndrome. Projectile vomiting is associated with disorders that increase ICP such as malignancy, hemorrhage, meningitis, or hydrocephalus. Finally, ask about associated symptoms. Essential historical points include associated fever, abdominal pain, jaundice, weight loss, prior surgery, diabetes, chest pain, and neurological symptoms. Fever is suggestive of an infectious etiology. In febrile infants, the presence of vomiting is a nonspecific finding and may be associated with sepsis, meningitis, pneumonia, pharyngitis, otitis media, urinary tract infection, or appendicitis. Associated diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, and fever suggest gastroenteritis. Vomiting with pain is more likely to be an organic cause. Although there is a large overlap in pain syndromes, a precise description of associated pain may help localize the underlying process. Severe abdominal pain that is colicky in nature and temporarily improves after vomiting points toward small bowel obstruction, while pain associated with cholecystitis (in the right upper quadrant, colicky, radiating to the right flank) and pancreatitis (constant burning epigastric pain radiating into the back) is unaffected by vomiting. Pelvic or groin pain might suggest ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, incarcerated hernia, or ureterolithiasis. Early satiety and postprandial bloating with epigastric pain are associated with gastroparesis and gastritis. Abdominal distention is suggestive of bowel obstruction or volvulus. The presence of neurological symptoms such as headache, vertigo, stiff neck, or focal neurological deficits suggests a central or intracranial cause of vomiting. Brainstem tumors are frequently associated with vomiting and are usually accompanied by cranial neuropathies. If vertigo (the illusion of movement) is the only associated neurological symptom, suspect a labyrinthine cause; however, be sure to consider more serious intracranial lesions or cerebellar stroke. If headache is the only associated symptom, migraine may be the most likely cause, but think also of subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, cyclic vomiting syndrome, and causes of increased ICP. Focal neurologic deficits suggest central nervous system (CNS) tumors, stroke, hydrocephalus, and brain abscess. Chest pain with vomiting is classic for acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction. When vomiting after fish ingestion is coupled with itching, hives, or wheezing, think of Scombroid poisoning, and with paresthesias and hot-cold reversal think of Cigateura poisoning. In the pregnant woman with hyperemesis, consider molar or twin gestation, hyperthyroidism, pyelonephritis, as well as intra-abdominal disorders. Physical Examination. The physical examination in patients with vomiting initially should focus on signs of dehydration such as poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, orthostasis, and hypotension. The general examination should assess vital signs, mental status, presence of jaundice or lymphadenopathy, and features of thyrotoxicosis. Check stool for occult blood, which suggests mucosal injury from ulcer, ischemia, inflammatory process, or malignancy. Auscultate the lungs for signs of aspiration. Examine the hands for dorsal calluses suggestive of self-induced vomiting. Other findings consistent with bulimia include lanugo, parotid enlargement, and loss of tooth enamel. Bronze skin, loss of axillary hair, and diminished temperature, pulse, and blood pressure are suggestive of Addison's disease. Inspect the abdomen for distention, visible peristalsis (a rare if virtually diagnostic finding of bowel obstruction), hernias, and scars from previous surgeries. Palpate the abdomen to localize tenderness, identify masses (such as the firm, ovoid epigastic "olive" of HPS) and hernias. Tenderness in the right upper quadrant suggests biliary or hepatic disease; in the midepigastrium, pancreatitis or peptic ulcer; and in the right lower quadrant, appendicitis. Costoverterbral angle tenderness should point toward a primary renal source such as pyelonephritis or stone. Auscultate the abdomen for increased or high-pitched bowel sounds in obstruction, absent bowel sounds in an ileus, and a succession splash over the epigastrium upon abrupt lateral movement or palpation in gastroparesis or pyloric obstruction. Finally, a neurological examination should be done to exclude CNS etiologies. Observe speech, cranial nerves, balance, gait, coordination, and strength. Look for nystagmus and consider the Dix-Hallpyke test when evaluating vertigo. Check for neck stiffness to rule out meningitis and inspect the fundi for papilledema suggestive of increased ICP. Diagnostic Testing. There are evidence-based consensus guidelines for the prevention and management of postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, but there is no similar guideline for the undifferentiated patient presenting to the emergency department with nausea and vomiting. Thus, recommendations for the use of laboratory studies and further testing cannot be firm and should be guided by history, physical examination, and clinical experience. Although electrolytes are usually unnecessary for the majority of cases, prolonged or severe vomiting can produce hypernatremia and/or hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. In addition, severe diarrhea can produce a metabolic acidosis with low serum bicarbonate. Consider measuring serum calcium in patients with known cancer or weakness, especially in the elderly. Measure glucose to exclude hypoglycemia in lethargic cases, especially children and the elderly. Low glucose and sodium with elevated potassium might indicate Addison's crisis. An elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to creatinine ratio is suggestive of dehydration, but can also be a clue to occult gastrointestinal bleeding. A complete blood count is not always necessary, yet might reveal anemia in those with bleeding or leukocytosis with an infectious process. Consider serum liver enzyme and lipase measurement in cases with upper abdominal pain and tenderness, or possible acetaminophen or mushroom ingestion, and serum ammonia in suspected hepatic failure or end-stage Reye's syndrome. Urinalysis is useful to screen for blood, white cells, bacteria, ketones, and elevated specific gravity. Serum may be better than urine pregnancy testing when considering ectopic pregnancy or radiographic imaging. Other laboratory tests to consider include blood alcohol, urine drug screen, serum levels of digoxin, theophylline or acetaminophen in overdose situations, and thyroid stimulating hormone in suspected thyrotoxicosis. Stool cultures should be obtained for cases of possible dysentery, presenting with fever, diarrhea, and blood in stool, and consider ova and parasite testing looking for Giardia in children attending daycare. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is essential in vomiting patients with chest pain, and even those without chest pain but risk factors for acute coronary syndrome, as well as a screen for QT prolongation if certain antiemetics are to be used (see below). Bedside ultrasound can be useful in identifying ascites, gallstones, cholecystitis (with gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, and dilation of the common bile duct), and hydronephrosis. Acute abdominal series radiographs can identify perforation and obstruction, although a significant number of cases will not have diagnotic findings on initial films if the perforation is small or the obstruction is early in its time course. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) is especially useful in evaluation of vomiting with abdominal pain in the elderly, appendicitis, possible necrotizing pancreatitis, mesenteric infarction and small bowel obstruction and should be considered in cases with persistent abdominal pain or tenderness of uncertain etiology. Head CT is indicated in vomiting patients with history of ventriculoperitoneal shunt or head injury, especially in the elderly, alcoholics and those anticoagulated, and those suspected of subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial hypertension, or mass. One bedside test for increased ICP is the use of the bedside vascular ultrasound probe placed over the eye to identify swelling of the optic nerve sheath. An optic nerve sheath diameter greater than 5 mm, measured 3 mm behind the globe, correlates with an ICP > 20 cm water.2 When evaluating an infant for possible HPS, consider insertion of an 8 F feeding tube to measure gastric aspirate volume. In one study, the aspiration of greater than 5 mL of fluid had a 91% sensitivity (95% CI 70 to 98%) and an 88% specificity (95% CI 77 to 94%) for HPS.3 These authors calculated the most cost- and time-effective algorithm for HPS evaluation was to perform ultrasound in infants with NG aspirates greater than or equal to 5 mL and upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) in those with less than 5 mL.3 Ultrasound diagnostic criteria for HPS include muscle wall thickness of at least 4 mm, a diameter of at least 13 mm, and/or a pyloric length of at least 17 mm. When considering possible intussusception, accurate diagnosis (and treatment) involves an air or barium enema following IV hydration and sedation. Ultrasonography is also diagnostic, and less expensive than air or barium enema, though not therapeutic. Few cases require surgical decompression when air enema is ineffective. Complications of Vomiting Dehydration. Dehydration can vary from mild to life-threatening, and is more prevalent in the very young and very old, especially with concomitant diarrhea. An adult with dehydration may present with weakness, fatigue, dizziness, altered mentation, or falling. For children, mild dehydration (< 3%) can occur without overt physical findings, and easily may be missed, whereas moderate dehydration (3-9%) is easily overestimated, but can manifest with tachycardia, diminished tears, dry mouth, delayed skin fold recoil (but < 2 seconds), slight delay in capillary refill, cool extremities, and decreased urine output.4 Altered mental status (lethargy, apathy, or unconsciousness), marked tachycardia (or even bradycardia when severe), thready pulses, sunken eyes, absent tears, delayed skin fold recoil (> 2 seconds), skin changes (such as minimal capillary refill, cool, mottled, or cyanotic extremities), and minimal urine output4 suggest severe dehydration (> 9%) and can lead to circulatory collapse when > 15%. The presumably most accurate method of assessing level of dehydration is by comparing the present to previous weight on the same scale, although this information is rarely available. Boerhaave's Syndrome. Boerhaave's syndrome is a spontaneous full-thickness rupture of the esophagus classically described as a sudden onset of severe chest, upper abdominal, or back pain following forceful or repetitive vomiting, but may also occur prior to vomiting in 14% of cases or without vomiting (but with coughing, straining) in another 14%.5 The Meckler's triad of pain, vomiting, and subcutaneous emphysema is seen in about half of cases, and Hamman's crunch may be present in 20%. Chest radiography is abnormal in 70-90% with widened mediastinum, pneumomediastinum, atelectasis, or infiltrate and pleural effusion, and occasionally pneumoperitoneum. Water soluble (Gastrografin) swallowing studies (esophogram or CT scan) are diagnostic. Endoscopy may be falsely negative. Complications can include mediastinitis, sepsis, pneumonia, empyema, persistent esophageal leak, and death. The mortality rate of 50% is related to delayed diagnosis. Mallory Weiss Syndrome. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with vomiting may be related to the Mallory-Weiss lesion, a linear tear in the mucosa of the esophagogastric junction. Although this lesion classically follows an episode of forceful vomiting, the lesion may be unrelated to vomiting and associated with regurgitation, increased abdominal pressure, or Valsalva maneuver, and is associated with alcohol consumption and portal hypertension. Although considered benign and self-limited, this syndrome may result in recurrent bleeding in 10%, necessitate transfusion in 25%, require therapeutic endoscopy or surgery in 10%, and result in death in 10% of cases.6 Because of the possibility of morbidity and mortality, gastroenterologist consultation is recommended. Treatment of Vomiting Enteral Rehydration. Consider oral rehydration with clear liquids containing sugar and electrolytes as the first option in most cases of vomiting that are mild, early, or resolving. In children with gastroenteritis with mild to moderate dehydration, consider oral rehydration when bowel sounds are present and there are no signs of obstruction, protracted vomiting, or other need for IV placement. Enteral hydration is safer and less expensive than IV hydration.7 Because of thirst, patients may attempt drinking large volumes of fluids, which can precipitate further vomiting. Drinking small amounts at a time may minimize this effect, such as starting with 5 mL of electrolyte solution (such as Pedialyte) every 5 minutes if younger than 4 years of age or 10 mL every 5 minutes if older. After one hour, increase the rate to 10 mL and 20 mL, respectively, every 5 minutes. If vomiting recurs, discontinue oral fluids for 30 minutes, then resume at the initial (lower) rate. If there are 3 or more episodes of vomiting, start IV therapy. Atherly-John, et al.8 found this method of oral hydration superior to IV hydration with regard to length of stay, nursing staff time, and parental satisfaction, without differences in hospitalization or relapse rates. Numerous oral electrolyte solutions are commercially available, and they typically contain 45-90 mEq/L sodium, 20-25 mEq/L potassium, 35-80 mEq/L chloride, 30 mEq/L of bicarbonate or citrate, and 2-2.5% glucose. Although oral rehydration solutions can be expensive, especially the premixed brands rather than powders, they are less expensive than IV therapy. The amount of fluids that should be replaced is calculated by combining an estimate of fluid loss plus the typical daily maintenance of about 150 mL/kg/days. Fluid loss from visible vomiting or diarrhea can be estimated by the following tips: one tablespoon will make a spot 4 inches in diameter on cloth, 2 oz. will make a spot 8 inches in diameter, and 8 oz. will saturate a 9x12-inch diaper. Another option to consider in patients reluctant to drink is insertion of an NG tube for enteral rehydration. Nager, et al.9 found rapid NG hydration with Pedialyte at a rate of 50 mL/kg over 3 hours to be similar in efficacy and labor intensity, yet with fewer complications and lower cost than rapid IV hydration with normal saline at a similar rate. Intravenous Hydration. Intravenous fluids are indicated in those patients with shock, severe dehydration, moderate dehydration with inability to tolerate oral fluids, gastrointestinal bleeding, ileus or obstruction, and severe or persistent gastrointestinal disorder (pancreatitis, cholecystitis). Consider IV fluids in those with elevated BUN, electrolyte abnormalities (such as hypernatremia, metabolic alkalosis), or other need for an IV catheter placement. Initially, isotonic fluids such as normal saline or lactated Ringer's are bolused in amounts of 20 mL/kg until vital signs and mental status are normalized. If large volumes are used (e.g., > 80 mL/kg), lactated Ringer's may be preferable over normal saline, which can lead to a hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, although the effect is of uncertain clinical consequence. Be cautious to avoid over-aggressive fluid resuscitation in patients with congestive heart failure or possible cerebral edema (e.g., Reye's syndrome). Although previous recommendations advocated cautious rehydration over 24-48 hours, rapid IV rehydration of children at a rate of 10 mL/kg/hr over three hours may be safe and avoid requirement for admission.10 Glucose-containing solutions have traditionally been avoided during intravenous rehydration. However, in children, glucose may have benefit. Levy, et al., found that a glucose-containing solution in a dose of D5NS at 20 mL/kg bolus, can reverse ketosis and hasten resolution of nausea, and decrease the chance of admission in children 6 months to 6 years of age.11 After the initial isotonic bolus, D5 with 0.45 saline if age older than 2 years or D5 with 0.33 saline if age younger than 2 years, with supplements of potassium chloride, can be given at 1.5 times maintenance amounts. Antiemetic Agents. Antiemetics are indicated when vomiting is persistent, likely to cause harm, and when not contraindicated. There are several classes of antiemetic medications available for use (see Table 4) including the anticholinergics, antihistamines, phenothiazines, butyrophenones, dopamine antagonists, and serotonin antagonists. The newest classes of antiemetics are the cannabinoids (dronabinol) and substance P antagonists (aprepitant), and have been effective in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), yet are not typically used in the ED.

There are few clinical trials comparing antiemetics in general ED populations with nausea or vomiting. In one double-blind, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of IV metoclopramide (Reglan) 10 mg, droperidol (Inapsine) 1.25 mg, and prochlorperazine (Compazine) 10 mg vs. placebo in 97 adults with nausea, droperidol was most effective at reducing nausea as measured by the visual analog scale, whereas metoclopramide and prochlorperazine were not different than placebo.12 By contrast, another double-blind, RCT of IV prochlorperazine 10 mg vs. promethazine 25 mg IV in adults with gastritis/gastroenteritis found better relief with prochlorperazine, shorter time to complete relief, fewer treatment failures (9.5% vs 31%), fewer complaints of sleepiness (38% vs 71%), and similar rate of extrapyramidal reaction.13 In a small, underpowered, non-ED RCT comparing IV promethazine 6.25 or 12.5 mg with IV ondansetron 4 mg for non-pregnancy, non-chemotherapy related vomiting in 46 adults, nausea and sedation scores were similar between groups.14 A recent RCT found similar efficacy between IV promethazine 25 mg and ondansetron 4 mg in undifferentiated nausea and vomiting in adult ED patients,15 although this dose of promethazine resulted in greater sedation. Because of the lack of clinical trials, the following general guidelines are suggested for the choice of antiemetic. Choose the Antiemetic Agent with the Least Side Effects.

Choose an Agent Based on Familiarity, Availability, and Clinical Experience.

Choose the Antiemetic Agent Based on Coexisting Conditions.

In refractory nausea or vomiting, rather than repeating another or higher dose of the same agent, consider medications that work on different receptors to avoid exaggerating adverse events. Although steroids such as IV dexamethasone 8-10 mg have been used for PONV and CINV,38* use in persistent, refractory vomiting in ED patients has been limited. Alternative Methods. Nonpharmacological methods of treating nausea and vomiting include acupuncture, acupressure, herbal therapy (ginger), massage, hypnosis, and biofeedback. Acupuncture at the P6 (Neiguan point) may have similar efficacy as traditional antiemetic medications.39 P6 is located two Chinese inches (the width across the thumb interphalangeal joint) below the wrist crease between the flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus tendons at a depth of 1 cm. Acupressure at P6 (Sea-Band) may be slightly useful for motion sickness as well as during pregnancy40 and can be purchased from boating stores, travel agencies, and some drug stores. Ginger has a weak 5-HT3 antagonistic effect, and may help cases of motion sickness,41 vomiting in pregnancy,33,42 and post-operative vomiting. Dosages of 250 mg PO four times daily to 500 mg PO three times daily are typical. Nasogastric Suctioning. The primary indication for gastric decompression with a nasogastric (NG) tube in the vomiting patient is to prevent esophageal, gastric, or bowel perforation, as when the obstruction is severe and increased intraluminal pressures are associated with wall ischemia, or in patients with suspected perforations (such as Boerhaave's syndrome). NG suction is not considered efficacious for pancreatitis or large bowel obstruction (with competent ileocecal valve).43 Because NG intubation has many potential complications, including pain, bleeding, perforation, and induced vomiting, the potential benefits do not outweigh the risks in those with mild obstruction or paralytic ileus. Conversely, do consider NG suction in patients with persistent abdominal pain, distention, and vomiting refractory to medications. NG intubation is relatively contraindicated in patients with recent nasal surgery or midface trauma, coagulopathy, esophageal varices (including recent banding or cautery), esophageal stricture, or inability to protect the airway (such as coma or loss of gag reflex). Avoid blind NG insertion in patients who have undergone gastric bypass procedures unless approved by their bariatric surgeon, since NG insertion could be difficult or result in perforation of the anastomosis. Patients consider NG intubation a painful procedure, perhaps worse than abscess drainage, fracture reduction, or urethral catheterization.44 In addition to discomfort and bleeding (which can be minimized by use of vasoconstrictive agent), NG insertion can result in tracheal or bronchial misplacement, perforation of the pharynx or esophagus, and pneumothorax. The discomfort of NG insertion can be minimized by local anesthesia with nasal viscous 2% or atomized lidocaine, nebulized lidocaine solution (1%, 2%, or 4%, not to exceed 4 mg/kg) via facemask, or nasal spray containing benzocaine or tetracaine-benzocaine-butyl aminobenzoate (Cetacaine). IV metoclopramide 10 mg prior to NG insertion may diminish both the nausea as well as the discomfort associated with NG tube placement.45 Conclusion Because of the broad range of potential etiologies of nausea and vomiting, an ordered approach to evaluation is necessary to maintain cost effectiveness and avoid misdiagnosis. In the ED, it is imperative to decide whether there is potential for an acute life-threatening emergency (see Table 2) and beware of the potential medicolegal pitfall of mislabeling appendicitis, meningitis, or sepsis as "gastroenteritis." Patients with severe, refractory symptoms, significant metabolic abnormalities, or evidence of an acute emergency require hospitalization for expedited evaluation and treatment. The emergency physician must also decide what diagnostic tests are indicated in the ED and which are appropriate for the outpatient setting. Not all vomiting requires IV hydration; oral hydration is often safer, cheaper, and as effective. Not all nausea or vomiting cases require antiemetic use; many patients have self-limited conditions Remember that all antiemetics have side effects, and the emergency physician needs to be prepared to treat serious medication side effects.

|